"I DEBUNK WELLNESS MISINFORMATION FOR A LIVING… SO, WHY DID I FALL FOR IT?"

I am lying on a bed in a small room that smells of incense, while a woman in ostentatious orange glasses sprinkles powder around my ear. She then takes my head and moves it from side to side. Seemingly satisfied, the process is then repeated with a variety of other powdered foods... until half an hour later (and £80 lighter), I emerge from her little studio (located above an estate agent) with a list of foods to avoid (cashews are “toxic” for me, apparently). And the strong suspicion I may have just been duped out of my cash.

In fact, there’s no ‘may’ about it. I have most certainly been duped: applied kinesiology – the allergy “diagnosis” method employed by that particular clinic – is widely derided as quackery, a health scam of the most obvious kind. And, yet, I’d found myself suckered into it. Something I never envisaged happening, given my job as a researcher focusing on online dis- and mis-information. [The difference between the two being intent: while disinformation is deliberate, misinformation is false or misleading information that may be shared inadvertently].

Over the last three years, alongside my side hustle as a yoga teacher with an interest in alternative health, I have professionally tracked conspiracy theories about COVID-19 and vaccines, investigated QAnon, followed far-right provocateurs and climate deniers, and deep-dived into the world of incels and trad wives. My two ‘lives’, as it were, could perhaps seem at odds with one another, but until recently, I believed they worked in perfect harmony – and that the yoga practice helped to take the edge off of the political and sometimes dark nature of my job. A job that also ensured I kept a healthy balance of open-mindedness and sceptical questioning when it came to that aforementioned interest in alternative health methods. Essentially, I had myself down as someone immune to online manipulation.

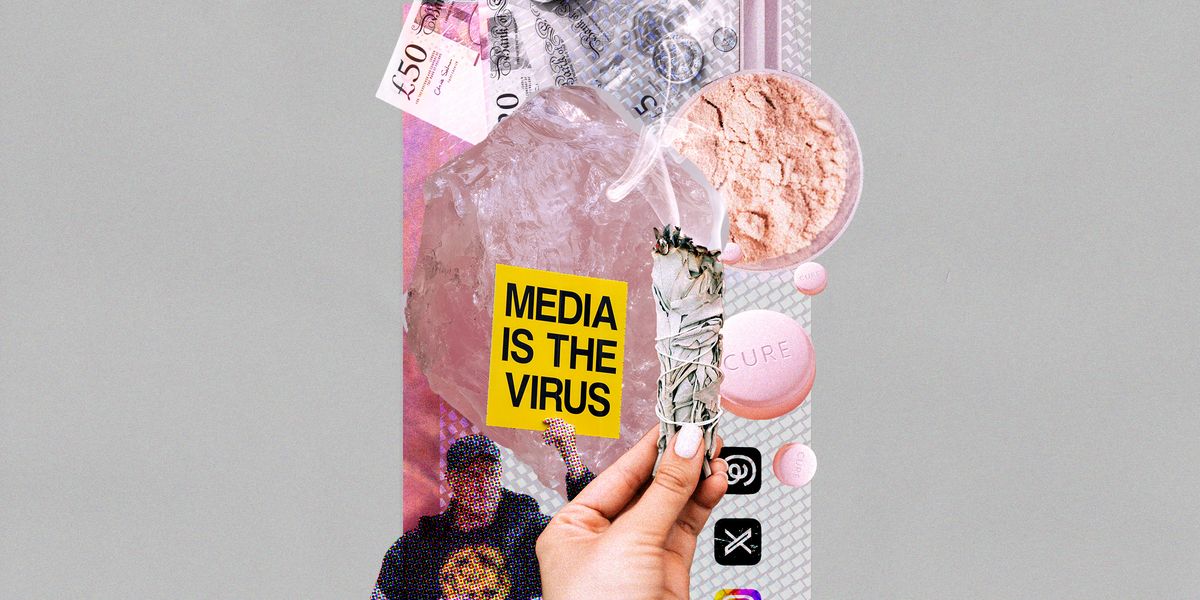

That was until I began exploring wellness dis- and misinformation, and uncovered the murky world of “conspirituality”, which blends conspiracy theories and New Age spirituality. As our lives moved even further online and fear and uncertainty about the pandemic took over, the wellness and New Age world - already dominated by the mantra that ‘everything is connected, nothing is as it seems and everything happens for a reason’ - embraced conspiracy theories.

Since then, that has only deepened.

FALLING FOR WOO-WOO

As the pandemic hit in early 2020, QAnon - the conspiracy theory which claimed that Donald Trump was trying to bring down a shadowy cabal of paedophiles - was moving into the mainstream, popping up in both my yoga classes and on my personal feed.

Curious to learn more, I started tracking conspirituality and wellness dis- and misinformation, following hundreds of influencers, from meditation coaches and self-styled gut health gurus to free birthers and carnivore bodybuilders who were spreading anti-vaccine views, along with wild claims about malevolent elites hatching plots to enslave the world population. From the first time I clicked that ‘follow’ button, social media platforms’ algorithms made it easy. The recommendations came thick and fast. And by telling myself I was only engaging with the accounts in order to debunk the misinformation they peddled, I glossed over my own vulnerabilities.

I suffer from a chronic inflammatory health condition, for which treatment options are limited, and experienced severe flare-ups in the early days of COVID. I also became a mother as the pandemic was coming to an end, and moved out of London to a city where I had no support network. Health issues, combined with the pressures of new motherhood and topped off by a cancer scare, stretched me to the limits. In short, I became the perfect target for wellness grifters.

Some research suggests that women may be particularly vulnerable to wellness misinformation and conspiracy theories. At the height of the pandemic, studies found women were more likely to express vaccine scepticism, and education status did not make them immune. Distrust of mainstream medicine and the search for alternative health practices among women is not coincidental either. A combination of medical gaslighting, under-investment in women’s health and poor understanding of certain conditions affecting women are just a few of the factors explaining why we are more likely to experience health anxiety than men.

Frankly, most of us fall for the wellness industry a little bit. Social media has become a Wild West of health misinformation, peddled by a wide range of self-styled experts and wellness coaches. Most of the claims sound innocuous, but plenty are the gateway to something much darker. The descent into believing conspiracy theories or losing faith in institutions, healthcare professionals or loved ones is a slippery slope: you can start out following a “mainstream” alternative health practitioner making dubious claims about gut health and quickly end up hearing scare stories about how governments are deliberately poisoning tap water.

Over weeks and months, I noticed how easily Instagram and TikTok’s algorithms would lead me from seemingly reasonable, although debatable, assertions about health to more conspiratorial narratives about medical institutions and “Big Pharma”. When contacted for commentary, Meta pointed to its misinformation policy which looks to tackle misinformation about vaccines and “harmful miracle cures for health issues”, and TikTok highlighted its community guidelines which cover “inaccurate, misleading, or false content” that can cause harm.

Yet, despite social media platforms having policies in place, wellness influencers are tough to police and still able to spread misinformation on a range of topics, from vaccines and health to the war in Ukraine. This algorithm prompting, combined with my defences having been ground down, saw me begin to try and manage my chronic condition by following the advice of the wellness influencers I was simultaneously debunking. Without really realising it, I was bingeing videos about health and nutrition, some of them produced by people whose ideology I had previously found dangerous and laughable.

I took advice from people I rationally knew were unqualified grifters and who had the words “hormone balancing coach” in their social media biographies (Dr Jen Gunter, a Canada-based ob-gyn who debunks myths about women’s health, has pointedly remarked that there is no such thing as “hormone balancing”). I experimented with infrared saunas, castor oil, reiki and various wellness protocols with limited (or non-existent) evidence to back them, spending hundreds of pounds in the process. I cut out food groups one by one. My feed became saturated with sponsored adverts for unregulated supplements.

Other questionable assertions started to sound convincing: that gluten/dairy/seed oils are inflammatory, and that mainstream medicine has an interest in keeping you ill. In hindsight, I know that my doctors did their best for me, but at the time it felt like I was taking tablet after tablet and still feeling unwell. With the chorus of the internet’s wellness community buzzing away in the back of my mind, I started to doubt the advice of medical professionals – ones who knew medical records inside-out, at that. The moment I pulled myself back from the brink? Only when I realised was even doubting the motivations of my own sister, who is a GP.

I am far from the only person to walk this road. Lydia Greene, a former anti-vaxxer and now trained nurse and co-founder of Back to the Vax, a website aimed at sharing evidence-based information about vaccines, experienced the leap from consuming health misinformation to developing a full-blown distrust of institutions, which descended into conspiratorial beliefs. She found herself stepping on what she describes as the “wellness hamster wheel” following a series of personal and health challenges.

After moving to a rural community with her partner and becoming a mother, she experienced flare-ups of Crohn’s disease, anxiety, and embarked on a journey to manage her condition with minimal medication. “I felt that I should exercise self-control,” she says. After feeling dismissed by public health services when she struggled to breastfeed her baby, Greene found support in online parenting groups – and among alternative health and wellness networks and influencers.

She says she spent thousands of pounds on diagnostic tests that were not rooted in science and rotated between highly restrictive diets, eventually subsisting on a diet of berries, nuts, and meat, and struggling to feed herself. “I became unwell on wellness,” she says. After her daughter had a bad reaction to a vaccination, she slowly slipped into anti-vaccine views. Greene says wellness and alternative health networks “provide a sense of community and that can be powerful when you’re isolated. After a while you start believing people based on no proof at all, because you just trust them”. Their likeability factor is key - researchers have shown that wellness influencers use a range of communication tactics borrowed from celebrity culture to appear relatable and authentic.

Yoga teacher and co-author (with Matthew Remski and Julian Walker) of Conspirituality, Derek Beres, says that at the heart of the wellness and New Age world, there is also a “naturalistic fallacy that everything natural is good, which primes people to think that the return to nature is the key to ideal health.” Charismatic leaders take advantage of that mindset to sell people products, he notes. “Once you start on that journey, you will start consuming more of the content coming at you from these influencers,” Beres says. Wellness and New Age influencers present everything as a dichotomy between what is natural (good) and what is man-made (bad): in that dichotomy, pharmaceutical companies become the bogeyman to rebel against.

“Once you start thinking of these companies as harmful it doesn’t take a big leap to start applying the same logic to other institutions, so you then start becoming suspicious of any power structure,” Beres adds.

FACTS VS EMOTIONS

The path from wellness misinformation to distrust of power structures is one Greene is familiar with, as her concerns about the dangers of vaccines led her to adopt ever-more conspiratorial views. “I started believing that pharmaceutical companies were making people sick to sell medication and vaccines, even if my personal experience did not match that statement,” she says. As the pandemic deepened and wellness influencers’ claims started becoming more extreme – see: promoting theories about Satanic elites out to harm children – something in her shifted. “I thought either I dig my heels further or I evaluate what I believe.”

As Greene started to distance herself from the movement, she slowly noticed the “cultic dynamics” of the wellness industry. When she expressed doubts publicly and talked about her change of heart, she became the target of online attacks from alternative health and wellness figures. In addition to providing a sense of online “community” at a time when many in industrialised countries experience loneliness and feelings of alienation, New Age and wellness disinformation networks and influencers can suck people into a bubble which feeds followers more of the same content. Stepping away from these beliefs can be difficult: challenging deeply held thoughts leads to “cognitive dissonance” and uncomfortable feelings, Greene says.

In her new book Doppelganger, Naomi Klein also remarks how conspiracy theorists “get the facts wrong but often get the emotions right”. They tap into the anger and powerlessness that so many of us feel in a world plagued by multiple crises, catching us at vulnerable moments and offering us a sense of individual control in a chaotic world.

So, is it any wonder that despite my career, I fell for their grift? Wellness influencers talk about poorly understood conditions that overwhelmingly affect women, including autoimmune conditions and those linked to reproductive health. With under-investment in women’s health it’s easy to see how women, who disproportionately experience medical gaslighting, can turn to influencers who promise solutions.

Life-altering experiences like parenthood can make people vulnerable too. Addressing these feelings with their content allows wellness influencers to give the impression that they - and they alone - are providing the nuanced conversations that are lacking in the real world. They can create a space where they genuinely “have your back” where mainstream institutions don’t, creating a divide. A distrust.

“Part of the appeal of wellness influencers is the way in which their fame is bound up with the internet's utopian ideals of democratic participation,” Stephanie A. Baker, who studies wellness influencers and teaches at City University in London, tells me. “By virtue of establishing fame online, they appear ‘just like us’ and unmediated by government and corporate interests.”

Wellness influencers’ condemnation of the greed of “Big Pharma” and calls to “follow the money” may have a grain of truth – as some conspiratorial narratives do – but rather than encouraging healthy scepticism, they aim to feed distrust of institutions and obscure the fact that these influencers (almost without fail) have something to sell, from coaching and retreats to supplements and “detoxification bundles”.

Mallory DeMille, who uses her TikTok channel to call out and deconstruct wellness misinformation, like me, also fell for wellness misinformation and spent years following a range of unorthodox protocols and detoxes, developing a “terrible relationship with food, exercise and [her] body” – despite having worked in marketing and knowing all the tricks of the profession. The key manipulation, she says, is that wellness influencers sell the problem and the solution. Health and nutritional science are incredibly nuanced and complex but “nuance doesn’t sell products,” she says.

“If I come across a wellness influencer who is trying to get me to diagnose myself with something, I ask myself if they’d financially benefit from me believing that,” DeMille adds. The motivations of wellness influencers who peddled misinformation are varied. While it’s easy to label a lot of wellness misinformation as “grift”, those same influencers have also become a key conduit for politicised misinformation.

After embracing QAnon during the pandemic, large sections of the wellness world now embrace broad-tent conspiracy theories about elites’ evil plans, including the “Great Reset” [the belief that powerful elites tied to the World Economic Forum are manufacturing various crises to achieve sinister goals and restrict fundamental freedoms]. They also increasingly sit on the right-wing side of the culture wars, increasingly embracing anti-trans views, climate scepticism and the return to traditional gender norms. Some wellness influencers overlap with and increasingly promote the ideas of the manosphere (misogynistic online communities), claiming that masculinity is under attack before dishing out discount codes for “testosterone-boosting” supplements.

My own anxiety around health and wellness is deep-seated. I am by no means free of it; however, I manage to distance myself from the content by unpacking the commercial and ideological motivations of some of these influencers, a time-consuming effort when platforms’ algorithms constantly nudge you towards that content.

Confronting my own vulnerability to misinformation has given me new empathy for people who are drawn to it, and for people whose personal circumstances make them susceptible to mistrust. If I could be seduced so easily, how much more attractive would it be for someone not expecting to encounter it? I have the motivation, time, and tools to sit down, unpick the lies, and follow the threads to see the ideologues and chancers for who they really are. Not everyone does.

Cécile Simmons is a researcher at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD). She writes about technology, dis- and misinformation, women’s rights, and the wellness industry.

2023-11-09T20:18:17Z dg43tfdfdgfd